Outdoor Geology Lab Tour: Meta-Argillite

Rock type

Metamorphic

Description

Gray rock that looks squished and flattened. On the flat surfaces of the rock, a second set of layers shimmer in lighter and darker silver and can be felt as slight bumps on the rock surface.

Figure 1: The meta-argillite at Scott Northern Wake Campus

Figure 2: The meta-argillite at Southern Wake Campus

Unique features

Narrow sedimentary layers (bedding planes) that you may have to look closely to see and foliation.

Figure 3: In this image, both the bedding planes (running top to bottom of the picture across a flat face of the rock) and the foliation layering (running right to left along the edge of the rock) are visible.

Figure 4: This image shows the foliation in the meta-argillite well. The foliation looks like layers that run from top left to bottom right.

Figure 5: Bedding planes in the meta-argillite. Notice that the layers are made of different materials. In some cases, the grains in each layer are different sizes.

How did it form?

Originally, this rock formed when quartz silt and sand particles mixed with volcanic ash from nearby erupting volcanoes as they settled to the bottom of the ocean floor. Once there, they became lithified into a solid rock. Later, intense heat and pressure metamorphosed the rock, giving it its foliation. Based on these interpretations, geologists have surmised that the meta-argillite formed on a volcanic arc that later collided with North America more than 600 million years ago.

How would a geologist figure out how it formed using rock characteristics?

There are two prominent features on this rock that a geologist would notice: the bedding planes, which are the silvery layers, and the foliation, which are layers that make the rock look squished.

Bedding planes are layers that formed when the original argillite (the rock that was metamorphosed to make meta-argillite) was forming. Argillite is a sedimentary rock composed of fine silt and sand-sized particles mixed with finer volcanic ash. The flat, even nature of the bedding planes suggests that all of these sedimentary particles were deposited in a relatively calm, wet environment that was not often disturbed by storms. Laboratory experiments have shown that small sediments, like silt and ash, do not settle out of water unless the water is nearly still. Conditions like these are found at the bottom of the ocean and in some lakes today.

Figure 6: Another image showing the bedding planes (black ballpoint pen for scale). The straight lines and thinness of these layers suggest calm, quiet waters where sediment could slowly accumulate.

Foliation is a characteristic that looks like fine layering in the rock. These layers form during metamorphism and often make the rock look like it might break into thin sheets. The foliation forms due to minerals being squished and flattened by the intense pressure that exists during metamorphism and by flat minerals (like micas) being rotated to line up perpendicular to the pressure. The presence of foliation will tell a geologist that this rock experienced the intense temperatures and pressures required to cause the minerals to squish and rotate in this way. The only natural forces known that can cause foliation like this are continental collisions.

Other interesting information

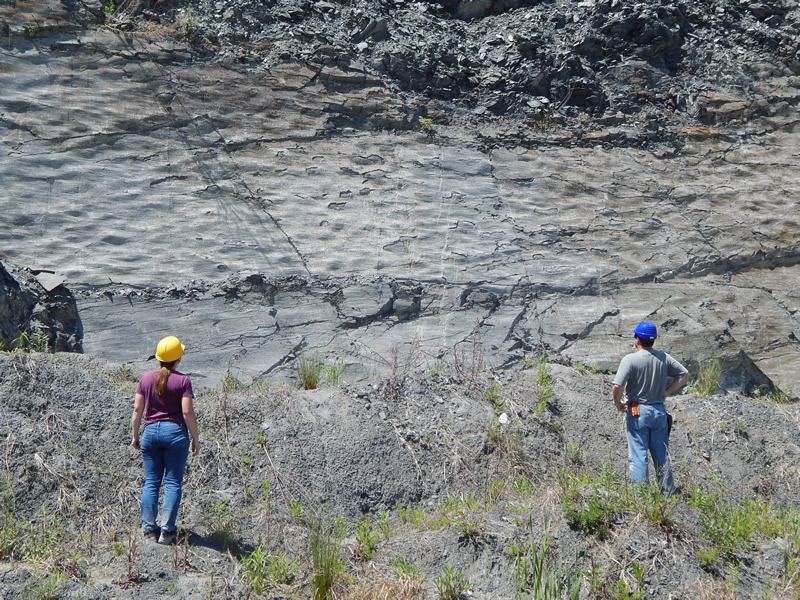

Despite undergoing metamorphism, this meta-argillite still retains a lot of its sedimentary rock characteristics. At the Asheboro quarry where this rock is abundant, we observed other interesting sedimentary features in meta-argillite rock faces that had not yet been removed from the ground. For instance, in one location, we saw an exposed wall of the rock that had current ripple marks preserved on it. These ripple marks must have formed when the sediment was deposited. Current ripples form when a current, like a stream or wave, moves fine sediment.

Figure 7: Wake Tech geologists Dr. Sara Rutzky and Tyler Clark examine the wall in the Asheboro quarry showing current ripples in meta-argillite.

2023 Footer Column 1

2023 Footer Column 2

- Wake Tech Mobile App

- Help & Support

2023 Footer Column 3

- Connect

919-866-5000

Contact Us | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Campus Policies | Site Map