Outdoor Geology Lab Tour: Rolesville Granite

Rock type

Igneous

Description

A blocky yellow-orange rock with speckles of white, black and tan. The surface of the rock is rough and brittle, and pieces fall off easily.

Figure 1: The Rolesville granite as it looks from the path.

Unique features

The visible grains (although these grains are smaller than those on some of the other coarse-grained igneous rocks in the Outdoor Geology Lab) and the brittle nature of the surface of this rock.

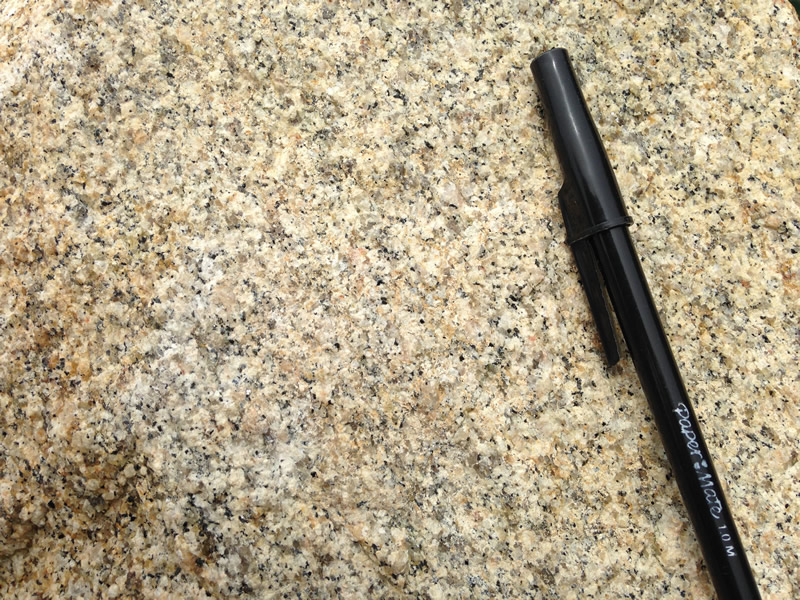

Figure 2: The surface of the granite, with a black ballpoint pen for scale

Figure 3: In this close-up view of the granite, you can see many of the different minerals. Each different color is a different mineral. Minerals include quartz, plagioclase feldspar, orthoclase feldspar and hornblende.

How did it form?

Granite is a coarse-grained igneous rock, which means that it forms from the slow cooling of magma deep within the Earth's crust. The light colors of the minerals found in granite show that the magma probably formed from the melting of continental crust.

How would a geologist figure out how it formed using rock characteristics?

Laboratory experiments have shown that the length of cooling of magma determines the size of the resulting mineral grains; the longer the cooling, the larger the minerals are able to grow. In the case of this granite, the minerals are visible but are not very large, maybe a few millimeters in length at their largest. The magma that cooled to form this rock cooled slowly underground to allow the minerals to grow that large, but the rate of cooling was faster for this rock than for most of the other coarse-grained igneous rocks in the Outdoor Geology Lab, since most of those have much larger mineral grains.

By examining rocks from different types of crust, geologists have discovered light-colored minerals make up the continental crust, while denser, dark-colored minerals make up the oceanic crust and much of the Earth's interior. The light-colored nature of the minerals in the granite suggests that this rock formed when continental crust was melted and then later cooled to form the rock. The melting of the continental crust was likely due to incredibly high heat generated by friction from two continents colliding. When this happens, huge sections of continental crust can melt. When the molten material cools again, it becomes a batholith (a large underground form) of granite.

Other interesting information

Since its formation, Rolesville granite has been subjected to slow but constant chemical and physical forces working to break it down. These forces are called "weathering." The Rolesville granite is particularly heavily weathered. Evidence of the weathering includes the rough surface texture and fractures that run through the rock. Additionally, the surface of the rock is brittle, allowing small pieces of the surface to break off periodically.

Figure4: Rolesville granite formed underground and is still mostly located underground. But even so, chemical and physical processes are acting on it to break it down to turn it into soil. This image shows the brittle nature of the surface of this rock as well as a fracture; both are the results of weathering.

Figure 5: This little pile of sediment at the base of the boulder fell off naturally due to weathering.

Rolesville granite rocks were discovered during the digging and blasting needed to construct of Building H on Scott Northern Wake Campus. There is no corresponding boulder at Southern Wake Campus, but other examples of this same boulder can be found as decorative stones around Building H. This granite is officially called "Rolesville granite" for how common it is near Rolesville, N.C. It is the rock that is found under our feet at Scott Northern Wake Campus.

2023 Footer Column 1

2023 Footer Column 2

- Wake Tech Mobile App

- Help & Support

2023 Footer Column 3

- Connect

919-866-5000

Contact Us | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Campus Policies | Site Map