Happy Holidays!

Wake Tech is closed December 24 through January 4 for winter break and will reopen January 5. Prospective students can still apply for enrollment online during the break, and continuing students can register for Spring semester classes, which start January 7.

Faculty Spotlight

Criminal Justice Technology

Following the Evidence In and Out of Class

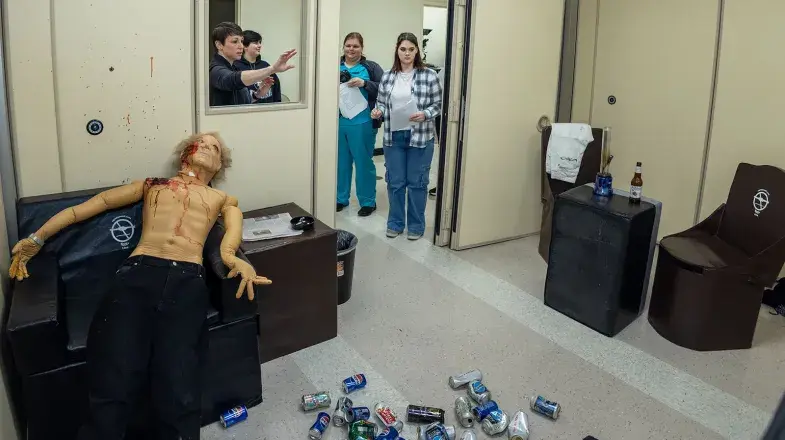

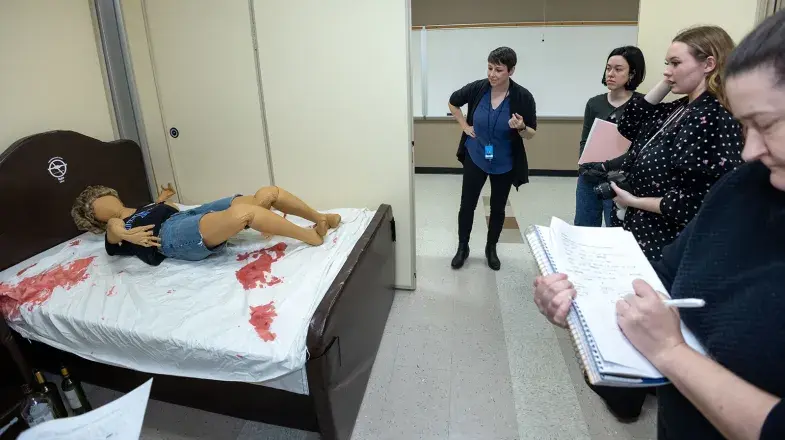

Empty beer cans litter the floor where a man sits dead in a chair in front of a television. Nearby, a woman lies dead in a blood-stained bed, and another man is face-down on a kitchen table, also dead.

Groups of Wake Tech students wander through the grisly landscape – actually a series of mock crime scenes staged in a classroom at the Public Safety Education Campus.

"Looks like he had a bad night," one student said about the dead man in the chair.

"Or he had been having a great night," another responded with a laugh, noting the large number of empty cans at his feet.

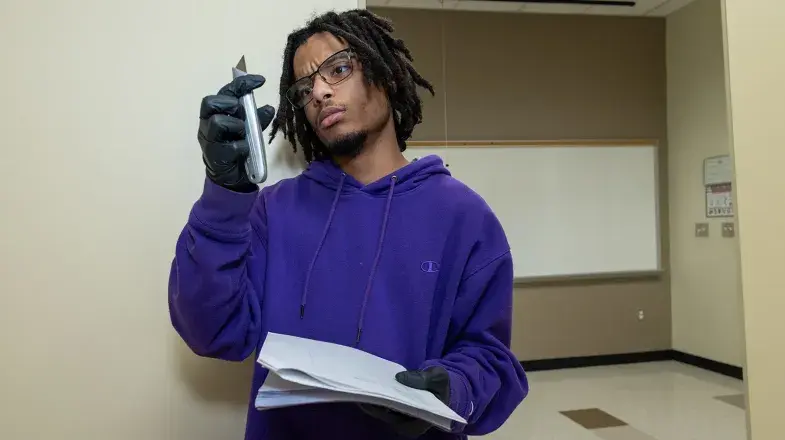

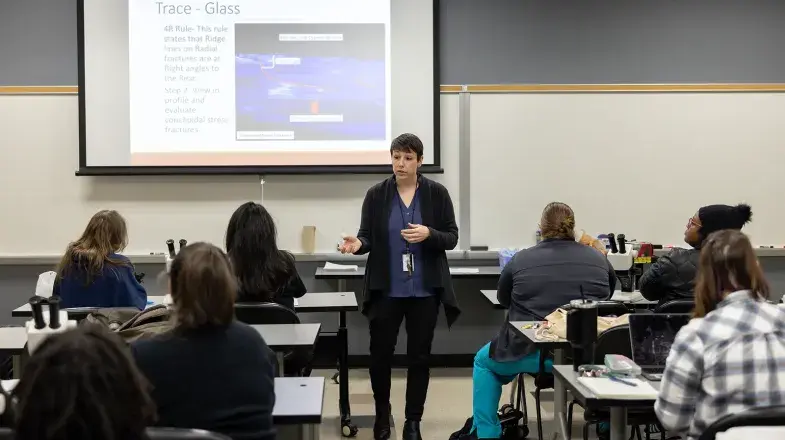

As they take photographs to document what they see, compile lists of evidence needing to be collected and formulate theories as to what happened, Forensic Science Instructor Sandi VanOverbake checks on each group's progress, asking questions about what they have found and what may be missing.

"We don't work the evidence to fit our theory of the crime," she tells the students. "We always simply follow the evidence."

VanOverbake has been following the evidence for years. A self-described "weird kid," she fell into forensic science early on after her parents bought her a book on fingerprinting. Her interest deepened in high school, when she got to dissect animal specimens in biology class and study them.

"I found anatomy absolutely fascinating. I wasn't grossed out like a lot of students," she said.

VanOverbake majored in biology and chemistry at East Carolina University, where she worked part time in a morgue, and went on to earn a master's degree in forensic science at the University of Florida. She then landed at North Carolina's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME), initially assisting with autopsies before working her way up to the position of death investigator, which meant responding to crime scenes when someone had been killed.

"It's the coolest thing in the world," she said. "You get involved in honest-to-God mysteries that need to be solved."

The job did have its drawbacks, however. The stench of dead bodies is hard to get past – VanOverbake lists "comfortable with death and decomposition" as one of her professional skills on her LinkedIn profile, right next to Microsoft Excel – and frequently witnessing the aftermath of violence takes an emotional toll.

"You absolutely have to compartmentalize mentally," she said, noting death investigators and law enforcement officers routinely support each other, especially after cases involving children and animals.

After a decade at OCME, VanOverbake wanted a job with fewer late-night calls to crime scenes. She joined HonorBridge, a nonprofit that handles organ donations, but quickly realized it wasn't for her.

"The grief and distress of family members wrestling with whether to donate a relative's organs was very difficult to handle," she said.

When an opportunity to teach forensic science and crime scene investigation in Wake Tech's Criminal Justice Technology program opened in 2023, she grabbed it.

"I always knew I wanted to teach, not children but at a college level," she said. "It's nice to have fresh minds and try to set them up for success out of the gate."

VanOverbake still occasionally fills in as a death investigator and often passes on lessons she's learned to her students, such as how to navigate the male-dominated law enforcement field – most of her students are women – and what to expect at their first crime scene involving a death.

"You can read a textbook, but you're not really ready until you understand what it means to experience a dead body or talk to a parent who just lost a child," she said.

Her students say VanOverbake's experience, communication skills and natural compassion combine to make her an effective teacher.

"She really cares about students and explains concepts very well," said Masha Tallant, who already has master's degrees in forensic science and forensic psychology but has taken a few of VanOverbake's courses to expand her expertise in the field.

Victoria Merida, who is pursuing an Associate in Applied Science degree in Criminal Justice Technology and plans to transfer to a four-year university to complete her bachelor's degree, agreed.

"She knows how to teach to students individually," Merida said. "She allows you to get things wrong and uses it to lead you to the correct process or answer, so you know the right thing to do from then on."

"CSI" and its spinoff TV shows have glamorized crime scene investigation to the point that it's now a hard field to break into, VanOverbake says. She has worked with OCME to get two students paid positions as assistants and hopes to open that door to more students in the future, providing critical job experience.

"Crime scene investigation is such a broad topic, from photography to evidence analysis," she said. "I'm just trying to help students find their people, find where they fit in."